« Drawing is a language; it allows us to express the inexpressible, the inexplicable, the unique,

and to convey its intensity and all its nuances through composition, the possibilities of which are almost infinite. If there is only one right word, there are a multitude of ways to express that word through drawing. » Jacqueline Royer |

At the source of language,

communication through images.

Preamble :

This work is an essay that offers a simple explanation fo the many artistic works left behind by prehistoric humans around the world.

Indeed, understanding the countless drawings left to us by prehistoric humans presents two difficulties: although the sites where these works are found are dated, this age is sometimes called into question by more recent dating methods. For example, those that have been dated using the uranium-thorium method have had their age pushed back by 10,000 years compared to the carbon-14 method.

Furthermore, how can we make sense of the many works that, in the same place, were created over long periods of time and feature very different images and styles depending on the era and the artist who produced them?

This is why, in order to understand these works, we will focus not on the place that brings them together, but on the evolution of their style.

Due to the complexity of the subject, which can only be addressed by specialists, we can only draw on a few examples, with the possibility of errors.

For this reason, this study should not be considered a scientific reference work, but rather a proposal requiring confirmation by prehistorians and linguists.

3 – The evolution of communication through graphic design :

It is reasonable to assume that cave paintings initially reflected a view of the world that was consistent with reality, as can be seen in the artistic development of children. However, little by little, this representation of the world came to be conveyed through painted or engraved symbols that were very different from reality.

From image to symbolic expression.

Why and how did this transformation from the representation of reality alone to symbolic representation take place ?

Before being able to date the appearance of different forms of writing historically, researchers believed that all writing originated in ancient Sumer, in Mesopotamia. This theory considered that, from this origin, it would have evolved over time through migration, the communication needs of different populations and the needs of trade.

Today, researchers agree that writing developed independently in at least four ancient civilizations:

- Mesopotamia, between 3400 and 3100 BC,

- Egypt, around 3250 BC,

- China around 1200 BC,

- and the plains of southern Mexico and Guatemala (around 500 BC).

With regard to Mesopotamia and Egypt, despite the proximity of the territories and the dates of the appearance of writing, historians now agree that the differences in structure and style between Mesopotamian and Egyptian writing suggest that they developed independently of each other. Mutual influence remains possible, but limited.

As far as China is concerned, bone and shell writing, used from the 15th to the 10th century BC on bones or shells, appears to be a completely independent invention.

To trace the possible evolution of images into writing, we will only consider the gradual evolution of images within graphic design itself, without concern for the date or location where these images were found. Indeed, the evolution of this graphic design depends above all on the artist, their creative abilities, and their cultural environment.

The emergence of writing.

« Cave paintings : art or writing ? »

A - The transformation of reality – From thought to writing :

a – Symbolic thought :For Francesco d’Errico, symbolic thought and language are inseparable in ensuring the transmission of thoughts to multiple interlocutors, including subsequent generations, which only language can do. The date of 40,000 years ago has long been accepted as the emergence of this form of thought.

However, symbolic thought emerged long before language, with the advent of vision. Indeed, brain cells had to receive and interpret certain electromagnetic waves (which then became ‘visible’) in order to transform the external object into an image, then name that image through sounds and cries. Another adaptation enabled the brain, through the acquisition of manual dexterity, to represent the symbolic object present in mental imagery on an external medium (communication through drawing).

Real object and brain activity (symbolic thought)

Motor brain activity and drawing.

Symbolic thought is therefore the brain activity that allows us to represent a being, an object or a fact outside of its presence. Present in the brain thanks to vision, we can already attribute this ability to encode information to all living beings that are capable of seeing, even though they are incapable of reproducing the object or sound frequency perceived in an image on a medium. Indeed, all living beings start from what they see and transform it into a motor reaction, such as hunting or fleeing.

Vision.

Motor action.

One could therefore argue that while language allows symbolic thought to be represented and shared, it is not directly responsible for the emergence of language. Other factors are at play, such as cooperation within species.

b - Speech, an instantaneous system of communication :

Succeeding other means of communication (gestures and emotional expression), spoken language has become indispensable for sharing symbolic thought, which relies primarily on visual recognition of behaviour (e.g. reassuring or threatening approach).

This language relies primarily on two of our senses, sight and hearing.

Its function can be compared to that of a computer's RAM, which allows information to be transmitted, the lifespan of which is usually limited to the current exchange.

Articulated language, as a form of sound expression, was initially used to warn of danger, then to convey the speaker's feelings. This is how we constantly use words to elicit in others a state of mind similar to our own, to make them aware of our perceptions, emotions, desires or orders.

In addition, we use words to convey not only practical information, but also knowledge and ideas which, thanks to memorisation, are passed on from one generation to the next and promote learning. Far from becoming static, this oral transmission of knowledge is able to evolve over generations.

c - Writing, a memoir that stands the test of time :

After developing a syntax that allowed language to evoke the past, the future, or even imaginary scenes, the next step was to record information so that it could be transmitted to distant places, either in time or space. Writing made it possible to develop this new capability.

Consisting of a coding of spoken language, it relies primarily on vision and, in its most advanced forms, uses symbols, signs, or letters capable of representing words and sentences. Appearing 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, it takes three forms: hieroglyphics, ideograms, and the alphabet.

It can be compared to the read-only memory of a computer.

Furthermore, as it is resistant to the passage of time, the strength of written information is that it retains its integrity over generations. However, it can freeze learning that would have naturally evolved thanks to new contributions.

While cries express the intensity of emotion experienced, articulate language gradually loses this ability as it becomes capable of informing others about the emotion experienced. Thus, in any war, there are those who experience the war and the feelings that accompany it, and those who know that there is a war but do not feel concerned by it.

Emotion.

Information.

Until now, articulate language had enabled humans to pursue and improve their integration into the world. Today, strangely enough, this highly effective language is undergoing a change. The thinking behind it is leading it in the opposite direction to that for which it was developed : designed to inform about reality, it can now become a driver of misinformation.

Until now, articulate language had enabled humans to pursue and improve their integration into the world. Today, strangely enough, this highly effective language is undergoing a change. The thinking behind it is leading it in the opposite direction to that for which it was developed: designed to inform about reality, it can now become a driver of misinformation.

« To communicate its perception of reality,

thought

began with vocal expression

and then extended into graphic expression. »

thought

began with vocal expression

and then extended into graphic expression. »

B – How did language evolve into writing ?

As speech is volatile, human communities, whose growth necessitated trade, sought to preserve information.Although the emergence of writing is relatively recent, it cannot be considered to have appeared suddenly. What preceded it ?

We can see that images appeared tens of thousands of years before writing, and that both have the same function: to describe the environment or describe experiences.

Thus, long before writing, tools and then graphic design showed us their ability to preserve information, to the point that we can now trace their evolution throughout geological eras. It is thanks to their works that the peoples who preceded us still speak to us today.

Let us examine how the transition from language to writing took place over the millennia.

To do so, we will use the learning and comprehension system that our brains are equipped with : analogical reasoning.

a – Reality without graphic expression :

What does “reality” show us, i.e. what do we perceive of our environment thanks to the extraordinary work performed by our brains ?

The scenes we observe seem simple. However, they depend on the coordinated action of billions of neurons. Some receive waves, others sort them according to shape or colour, and still others reassemble them into two- and three-dimensional images.

However, this image does not exist in the brain. Only regions in which neurons are active can be distinguished by electroencephalogram.

In the distant past that interests us, images were constructed in the same way as today in the brain of the individual, whether animal or human, in the form of brain activity: they did not need to be reproduced on a medium because they were sufficient for immediate adaptation to environmental conditions.

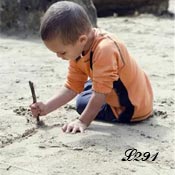

Today, animals do not need to draw or write to remember favourable locations, how to get there, or to share information. Humans, on the other hand, need images or writing, and they start doing so from childhood, even though, like animals, they can only express themselves through sounds and body language.

b - The emergence of drawing :

Could the reasons that led these extinct civilisations to leave an indelible mark of their passage be the same as those that drive children to try to represent what they see?

Why do children need to draw lines on a piece of paper and then draw pictures? Discovering the reason for this might help us understand why prehistoric humans did the same.

The most logical explanation seems to be that they simply wanted to draw the world around them. Today's children's drawings are full of reproductions of the things and beings that surround them: houses, cars, family...

|

|

There are many reasons why humans might have carved into stone: to occupy a moment of idleness, to remember an important event, and, later, to communicate with their peers by marking their territory.

But it is more likely that the very first images never had a communicative purpose. As we see in children, curiosity and the discovery of colours and the surrounding world may simply have made humans want to represent what they saw.

It may even have been automatic, like the urge to draw in the sand or doodle on a piece of paper while we are on the phone.

It was much later, when groups became more important, that communication became necessary. The static image then followed the rise in demand.

It was gradually enriched with different images to convey different situations and thoughts, resulting in an increasingly sophisticated representation of reality.

This richness appears in all the images that preceded the advent of writing.

To summarise the situation, a general chronology of human evolution and creative abilities has been recorded in engravings and drawings over hundreds of thousands of years, but this general evolution masks the evolution of creative thinking, which differs between human groups depending on their activities (hunting, farming, etc.), migrations, and environment, but also between each individual.

Inspired by the evolution of children's drawings, we will therefore attempt to understand the graphic expression of the humans who came before us.

In doing so, and in the absence of knowing why prehistoric man engraved or drew, we can try to understand how his graphic art evolved and grasp the development of his thinking over the millennia as he gradually understood the importance of images in communicating his knowledge.

By following the evolution of their manual dexterity, we will discover how their minds interpreted the world, from scribbles to the discovery of perspective.

Their earliest creations are very ancient and constitute what we now call rock art and cave art.

It goes without saying that such a proposal cannot aim to challenge current research on the subject, but it could suggest a simple interpretation of our predecessors' creations, thus complementing the range of scientific theories.

c – How do children's drawings evolve ?

To carry out this comparative study, we will draw on the work of Georges-Henri Luquet (Le dessin enfantin, 1927), et Jacqueline Royer (Que nous disent les dessins d’enfants ? 2005) to assess the progression in representations of Neanderthals and Sapiens.

We will then leave it to researchers to confirm or refute the validity of this work.

1 - Children's drawings between the ages of one and two - discovery :

From the age of one, armed with a pencil, children begin to explore their tools and start scribbling on paper. What could be more magical than seeing lines appear on a blank sheet of paper? This discovery is complemented by the discovery of colours.

They do not yet know how to hold their pencil, but they learn to control the movements of their hand as their lines gradually become intentional.

This stage lasts until the age of 3.

(12 mois)

(12 mois)2 - Between two and three years old - accidental realism :

During this period, the lines go in all directions.

The child does not seek to reproduce or represent something real. He explores the results obtained with the materials and different tools at his disposal.

From these scribbles, the child will begin to direct their strokes, creating zigzags, straight lines or curves. It is after this period of experimentation that our young researcher's drawings will begin to resemble objects. Among these varied lines, a recognisable shape may appear, constituting accidental realism.

Lignes brisées.

Lignes brisées. Arrondis.

Arrondis. Yeux.

Yeux.Gradually, the random act will become intentional and representative. The stick figure is sketched out.

3 - Between three and four years old :

It is at this age that the ‘tadpole puppet’ really appears.

The child will begin to represent their family, indicate who the members are and distinguish them by varying the size of their characters.

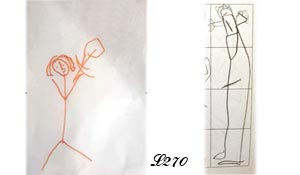

(3 - 4 years old) The tadpole puppet according to J. Royer.

Around the age of three, he begins to control what he does and manages to copy simple shapes.

It is during this period that the first stick figures also appear.

4 - Between four and five years old - failed realism :

Around the age of four, drawings become narrative. We can recognise what the child wanted to represent and guess at a story.

Faces become expressive.

In addition to circles, the child begins to draw rectangles and triangles.

(5-6 years old) The stick figure according to J. Royer.

They draw based on what they know. The character will be more detailed, with hair and a face. Proportions are not yet respected: what is important will be drawn larger

As his own body image becomes clearer, he completes the bodies of his characters. Similarly, his landscapes are enriched with flowers, castles, characters from his fairy tales, and the sky is adorned with sun, stars and clouds.

He is thus able to represent both the world around him and an imaginary world.

5 - Between 5 and 7 years old – intellectual realism :

The child draws all the shapes he knows, abandoning what he sees, and his technique becomes richer.

The body schema of his characters is complete, the face expressive. He adds details to his setting.

We can see that he uses drawing as a means of communication and can use colours to convey emotions.

(6 years old) The stick figure according to J. Royer.

6 - Between 6 and 8 years old – conventional drawing :

Representation of puppet characters.

7 - Between 7 and 9 years old – visual realism :

The 7-9 age group experiences a significant leap in the realistic representation of details. The child uses the ruler and eraser and dresses his characters.

He respects the details of the decor and the emotional expressions he has experienced (smiling mouths, angry eyebrows, etc.).

The sky is filled with clouds and birds, and the ground with trees and flowers.

The drawing becomes more organised, influenced by social life, with nature appearing in the form of plains and mountains. Cars are on the roads and traffic lights are not forgotten. Planes fly in the sky, and anything that has been forgotten is added to fill in the gaps.

(10 ans).

8 - Between 9 and 12 years old :

Proportions are respected with the addition of simple perspectives.

At this age, children are able to express complex ideas and emotions in their drawings.

9 - Between 12 and 13 years old - the critical stage :

Social influence begins to replace creative spontaneity. Children criticise their work and may be disappointed with the results.

As they discover the world, children try to communicate what they see.

After sharing through words and attitudes, they use drawing to remember and communicate.

However, while drawing provides a satisfactory view of reality, it does not express feelings well and struggles to convey the richness of thought. It is social input that will enable children to make their drawings more expressive.

It is these same external influences, particularly school, that will later enable them to learn to write.

Thus, it is by developing our knowledge of children and how their writing changes as their personalities evolve that we can better understand the evolution of humans and their writing over time.

In the meantime, we will simply try to compare a number of cave and rock art representations with the main characteristics of children's drawings.

« The way in which children's drawings evolve

can give us an indication of the evolution of cave art representations. »

can give us an indication of the evolution of cave art representations. »

d – The reality depicted by the petroglyphs :

Lower Palaeolithic (approximately 800,000 to 300,000 BC)

Middle Palaeolithic (approximately 300,000 to 40,000 BC),

Upper Palaeolithic (approximately 40,000 to 9,500 BC), emergence of figurative art.

Mesolithic: 9600 to 6000 BC

Neolithic: 6000 to 2300 BC: Pottery

Bronze Age: 2300 to 800 BC

Iron Age: 800 to 50 BC

Antiquity: 50 BC to 500 AD

Middle Ages: 500 to 1500

Modern era: 1500 to 1789

Contemporary era: 1789 to the present day

When did early humans first develop the ability to make and use tools that would later lead to the emergence of cave art ?

We know that the first sophisticated tools, bifaces, appeared 1.7 million years ago, during the Lower Palaeolithic period, which marks the beginning of the Stone Age. They represent an important step in human evolution, the ability to shape rock into useful objects: the multi-purpose tool was born.

Once humans had acquired the ability to shape objects, they were able to reproduce elements of their environment on a medium and then communicate their knowledge through the images they produced.

|

|

Biface. |

Striking flint. |

Although not part of language, bifaces foreshadow the advancement of early humans' thinking and their ability to understand shapes in order to model an object.

Thus, after creating the tool and revealing its creative function, it is thanks to the tool that the human brain will reveal, through the hand, its ‘artistic’ ability.

What will humans do with their tools? The same thing that children do today with the crayons they are given.

If they don't have crayons, they will find inspiration in soft soil or sand.

1 - Rock art, similar to a child's drawing ?

The term ‘rock art’ refers to all works created by humans on rocks, most often outdoors. It is distinct from cave art, which is created on cave walls (indoors), and also from portable art (which can be moved). These works are not the product of a specific population, but appear to be universal.

This prehistoric art is characterised by the use of several techniques:

- engraving : artists hammered a rock surface with a hard stone (the hammer), creating what is known as a petroglyph.

The earliest examples date from the end of the Middle Palaeolithic period (approximately 300,000 to 40,000 years ago),

- painting : drawings were made with coloured powders from crushed minerals. Using a reed or hollow bone, the coloured powders were blown onto the surface after handprints had been made or to represent details in animal drawings.

This figurative art developed at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic period (between 45,000 and 30,000 BC).

Rock engravings are the oldest representations that have been discovered. However, it should be noted that although colours were used in such distant times, they may have been erased over time.

What we can conclude is that petroglyphs constitute the most enduring memory, and that by studying the chronology of images based on their artistic maturity, it is possible to assess the evolution of each cultural group, as well as its migrations.

While the manufacture of bifaces can be dated and their usefulness understood, the origins of cave art remain more obscure.

In the Daraki-Chattan cave, located in central India, evidence of early human activity has been found in geological layers. In the early Palaeolithic period, this cave not only served as a tool-making workshop, but also contains the richest collection of cup marks known in the world. These cup marks, along with stone hammers found at various levels of the excavation, are considered proof of the existence of art as early as the Palaeolithic period. Yet they still hold their secrets.

All the evidence available today shows that the development of human cognition and artistic production had been underestimated.

Cup marks on a vertical quartzite wall in the Daraki-Chattan cave, India,

(Lower Palaeolithic)

(Lower Palaeolithic)

This rock art is estimated to date back more than 290,000 years BCE.

Similar works have been discovered in the Auditorium Cave in Bhimbetka, also in India.

Petroglyphs at Bhimbetka (290,000 years old (possibly 700,000 years old) BCE.

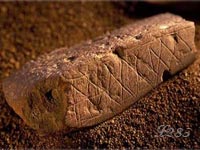

Closer to home, a 75,000-year-old block of ochre found in Blombos, South Africa, features geometric patterns engraved in the shape of cross-hatches. Also considered artistic representations, they could nevertheless have the same meaning as the pencil strokes made by a child under the age of two.

|

|

Grid pattern engraved on a block of ochre in Blombos, South Africa (-70,000 years).

Having understood how children's drawing evolves as they learn about life, how can we interpret the evolution of graphic design in pre-human species ?

To do this, we will disregard the chronology linked to the dating of sites and study only the evolution of graphic art itself. This will then take on its full meaning by representing the artistic maturity of a human group at a given time and place.

This is not an assessment of the artist's mental age, but an evaluation of their graphic art by comparison with the evolution of children's graphic art.

In the case that concerns us here, prehistoric humans were adults with survival skills in the natural environment that were far superior to our own as modern humans.

Although we cannot yet draw any conclusions about the purpose of these cup marks, whose origins are too ancient, we can nevertheless draw a parallel between certain petroglyphs and the first sketches made by children. It is therefore on the basis of these drawings that we will attempt to understand the history of writing and, perhaps, determine its origin.

Finger drawings on soft rock could be a starting point. These have been found in the French cave of La Roche-Cotard and have been dated to over 57,000 years old. Neanderthals were the last occupants of this cave.

Finger drawings on soft rock.

Here we find similar markings made in the sand by a child, which could have been made by anyone idling on a beach.

Furthermore, as is the case with a child aged 1 to 3 who scribbles on a sheet of paper, Neanderthals may have “scribbled” on the walls of their caves.

(Child aged 1 to 3)

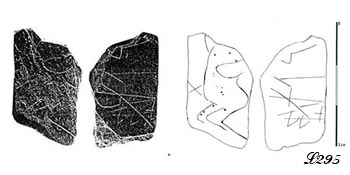

Other engravings with straight lines have also been attributed to Neanderthals.

In Gorham's Cave, located east of Gibraltar, there is an engraving that was covered with sediments containing Mousterian tools estimated to be 39,000 years old, at a time when Neanderthals were alone on the Iberian Peninsula.

The straight lines could suggest a confident hand, but on hard rock it is easier to draw straight lines or follow pre-existing fault lines. Percussion is more suitable for curves, as we shall see later with more elaborate representations.

(Child aged 1 to 3)

Neanderthal engravings in Gorham's Cave,

Straight lines requiring a tool.

Neanderthal engravings in Gorham's Cave,

Straight lines requiring a tool.

LThe child expresses himself in the same way, but he needs a malleable medium.

More detailed lines dating from the Mesolithic period (-9600 to -6000) in the sandstone massifs of the Paris Basin are also considered to be ‘schematic art’, but the abundance of lines makes it impossible to determine units and their relationship, unlike realistic art, whose style and content are characterised.

Assertive graphic design, but still partially random.

Mesolithic petroglyphs in the sandstone massifs of the Paris Basin.

Mesolithic petroglyphs in the sandstone massifs of the Paris Basin.

However, it may remind us of the drawings made by children between the ages of two and three, where, starting with scribbles, the child begins to direct their strokes, creating zigzags, straight lines or curves.

This is what we find in the rock shelter at Noisy-sur-Ecole (France), where the drawings are organised.

(Child aged 2 to 3)

«If we compare drawing to writing,

the lines are the equivalent of letters that do not yet form words. »

the lines are the equivalent of letters that do not yet form words. »

Elsewhere, the thread-like engraving denotes confident and intentional control.

(Child aged 3)

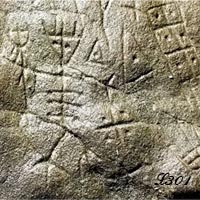

Prehistoric Camuni people, Iron Age – 1st millennium BC

Prehistoric Camuni people, Iron Age – 1st millennium BC

In the Tardenoisian site of Bois de Chinchy, a small slate plaque features lines on one side and random marks on the other, which have been interpreted as a female silhouette, although this could just as easily be a case of pareidolia.

Accidental realism. (3-year-old child)

Luquet refers to this association between a random line and the appearance of an object as the stage of “fortuitous realism” in children.

Thus, in geode II of Le Bulou, a headless man (a) and a woman (b) have been identified in the grid, but the whole could just as easily represent a fish.

|

|

« Sometimes lines come together, seemingly creating images,

just as letters can come together by chance

to create words. »

just as letters can come together by chance

to create words. »

Amidst all these lines, new shapes emerge, as in the Niche des Cabanes in Essonne, France.

Straight lines curve and combine with parallel lines to evoke an animal.

Failed realism (4-5 year old child)

Mesolithic grids and recent engravings: a star and a sketched animal.

Mesolithic grids and recent engravings: a star and a sketched animal.

« Vague images emerge,

as, later, written words will do. »

as, later, written words will do. »

The drawing becomes more refined, and while some shapes remain obscure and are described as symbolic, others evoke animals, such as a deer here.

We are at the stage of a 4-5-year-old child : the intentional act becomes representative.

(4-5-year-old child)

Deer in the cave at Noisy sur Ecole (Ségognole shelter, Seine-et-Marne, France)

Deer in the cave at Noisy sur Ecole (Ségognole shelter, Seine-et-Marne, France)

« When the lines come together to represent a known being,

the word immediately springs to mind: “deer”.

One day, this drawn word will be written with ideograms and then letters. »

the word immediately springs to mind: “deer”.

One day, this drawn word will be written with ideograms and then letters. »

However, depictions of animals in the decorated caves of the Fontainebleau forest remain rare.

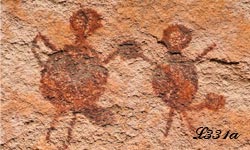

Elsewhere, circles have appeared and are filled with details, mirroring the shapes of tadpole guy.

"Tadpole puppet " (age 3)

Petroglyph of Taíno Indians in a cave in Los Haïtises National Park (Dominican Republic)

Culture disappeared with the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492.

Petroglyph of Taíno Indians in a cave in Los Haïtises National Park (Dominican Republic)

Culture disappeared with the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492.

Stick figure and triangles (4-5 years old).

Representation of what could be a shaman holding a sistrum (Fontainebleau Forest).

Although the hardness of the rock requires straight lines or following natural lines,

the presence of this figure denotes the narrative aspect of the glyph.

Representation of what could be a shaman holding a sistrum (Fontainebleau Forest).

Although the hardness of the rock requires straight lines or following natural lines,

the presence of this figure denotes the narrative aspect of the glyph.

This image can be compared to similar figures created in another era and in another place.

Stick figure (3-4 year old child)

Petroglyphs in the Gobi Desert (-15,000 years)).

Petroglyphs in the Gobi Desert (-15,000 years)).

Let's forget about the aliens from Roswell : we only have a well-proportioned puppet figure.

(Child aged 6-8).

Rock art from ancient Peru (-6000 to -2000 years old).

Rock art from ancient Peru (-6000 to -2000 years old).

Thus, depending on the region and at very different times, similar designs can be found.

Below, while retaining a thread-like design, the representative drawing begins to be enriched with vertical stripes by hammering the rock.

The animal has a youngster whose coat displays the same distinctive mark.

Intentional and representative act (4-5 years old). The drawing is recognisable.

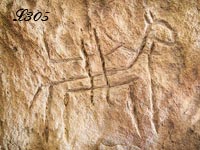

Rock carvings in Uzbekistan dating from the Mesolithic period (-9600) to the end of the Middle Ages (+1500).

Rock carvings in Uzbekistan dating from the Mesolithic period (-9600) to the end of the Middle Ages (+1500).

Suddenly, the scene no longer represents just a living being, but evokes a scene from everyday life. The artist tells us that he has domesticated the animal.

Representative drawing (4-5 years old).

Gobustan National Park – Azerbaijan (-10,000 years).

Gobustan National Park – Azerbaijan (-10,000 years).

« In the form of drawings, words (horse, rider) begin to come together,

sketching out a grammar. »

sketching out a grammar. »

In addition, this artist tells us that he has sophisticated tools to make his hunting more efficient. The expression of his graphic language becomes increasingly explicit. Millennia later, we are still able to grasp the general meaning and put words to his representations, even if we cannot yet access the artist's own story.

Hunting. Narrative drawing (4-5 years old).

Petroglyphs in the Gobi Desert.

Petroglyphs in the Gobi Desert.

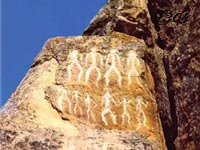

From simply representative, drawing became narrative.

Now, man is no longer alone ; he is part of a tribe and, holding a child by the hand, he has a family – collective consciousness is now expressed in graphic art. Emotion may well begin to be expressed in the work, with the emphasis on the bond that unites human beings.

|

|

Narrative drawing (6-8 years old).

Stone sculpture in Gobustan National Park. Azerbaijan (-10,000 years).

Stone sculpture in Gobustan National Park. Azerbaijan (-10,000 years).

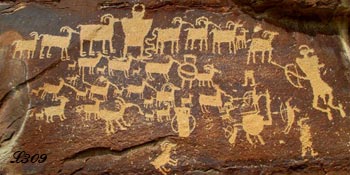

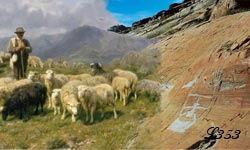

Narrative drawing is gaining momentum. Like a photograph of a moment in life, we see a hunting scene or, perhaps, shepherds and their flock.

(Children aged 8-12).

The great hunt. Petroglyphs in Nine Mile Canyon – Utah (+1000).

The great hunt. Petroglyphs in Nine Mile Canyon – Utah (+1000).

The image is no longer limited to representing a character through a drawing or an articulated sound, equivalent to one of our words. A story emerges from this image, that of a herd, its shepherd and armed guards or potential thieves. This story can be told by each of the participants according to their place in the event, and each narrative will contain its share of emotion, the pleasure of shared life, or the fear felt during an attack.

Like any adventure recounted during a family gathering, the story belongs to the person who expresses it, whether through spoken language or drawing.

« Narrative drawing is the story we tell to those who have lived it,

or who can understand it. »

or who can understand it. »

Let us now revisit all these engravings through the eyes of the child we once were.

2 - The link with children's language :

If we recapitulate the evolution of graphic design, we have just seen that the hardness of the rock initially imposed simple lines limited to the contours and then the filling in of the central character.

Then, simple images, each with the same meaning as one of our words (sun, animal, man, tribe, etc.), were gradually assembled to describe an event.

This event could be reduced to a few ‘words’: ‘the shepherd and his flock protected by armed guards’; but it can also have the value of a long story based on what is a photograph of an event fixed on stone. Here, language is not constructed from juxtaposed signs like our written languages, but as a global event that everyone can ‘read’ in their own way, depending on whether they are observers of the scene or one of the characters present (shepherd, sorcerer, thief or armed guard) recounting their experience of the event.

Let us remember the the language of the Aïbos.

We have seen that the actual image precedes language, with words coming secondarily to designate the image. Just as animals use sounds to describe their environment or express how they feel, it is likely that prehistoric humans also had sounds or words (just as the Aïbos have developed) to designate each element of their environment and, later, each object drawn: horse, bison, lion, man, bow, deer..

The image shows the object or scene in the same way that the word allows us to imagine the object and the language to visualise the scene.

L'image :  |

L'image :  |

The word : ‘drum.’ |

The language : ‘Men dance to the sound of the drum.’ |

« The word describes what we see in a transitory way, the image maintains the memory.

Preceding written words,

drawings were the first symbols representing the living world and real-life situations. »

Preceding written words,

drawings were the first symbols representing the living world and real-life situations. »

We have thus touched on a new element, that of the link between image and word, and once again it is the development of children's language that will show us how images gradually came to illustrate the words used by humans to describe the world in which they lived.

Let's recap the development of language in young children.

We know that foetuses come into contact with language as early as during pregnancy. In fact, they can hear from the sixth month of pregnancy onwards. Even if they cannot understand the meaning of the sounds and words they hear, they can sense what the intonations express...

This is why, from birth, babies confirm this learning through their sensitivity to prosody, i.e. the intonation, accentuation and rhythm of language. However, at first, they can only express themselves through sounds to share what they are feeling.

Then they babble, and we don't always understand them. It is only at three months that they begin to pronounce random syllables, which they will master at five months.

It will take another eight to twelve months before we hear them say their first word. This will often be ‘mummy’ or ‘daddy’, the word they have heard most frequently.

From the age of one, toddlers will say words that refer to things in their environment. At 18 months, they will understand between 65 and 110 words.

This is when they start to combine two words that have meaning, for example, they will ask ‘where Daddy ?",

Children become very talkative, enjoying showing off the extent of their vocabulary.

During their second year, they will increase the number of words they have acquired during their first year tenfold.

It is around the age of 3 that children really start to talk, using constructed sentences and repeating expressions they hear. They have acquired language.

How, then, can we understand the evolution of graphic design in light of the development of children's language ?

(Prehistoric man's drawings remain incomprehensible).

Similarly, at three months old, children train their speech organs, filling their environment with babbling that no one understands.

(Uncertain writing develops, constructed forms appear, and the first comprehensible representation is born).

At one year old, children's language becomes structured and they say their first word.

(Other understandable images appear : ‘ibex’, ‘hunter’.

However, the meaning of the image remains uncertain : is the ibex being hunted ? Or is it being protected from an approaching predator ?).

At 18 months, the child associates two words, giving more meaning to their language.However, the meaning of the image remains uncertain : is the ibex being hunted ? Or is it being protected from an approaching predator ?).

(The drawing of the prehistoric man allows them to develop the story they are telling).

At 3 years old, children now tell us real stories.

(Like a photograph, the drawing describes an event,

but this event can only be truly understood by those who experienced it).

At 4-5 years old, the child's language allows them to tell a complex story, even if the arrangement of ‘words’ is still jumbled.but this event can only be truly understood by those who experienced it).

The child's parents will understand this better than strangers to the family.

3 - The possible emergence of counting :

While images enabled thoughts to be conveyed, they also contributed to the development of calculation. Indeed, how can one calculate without the means to refer to something concrete? Graphic symbols provided the essential fixed reference point.

We previously mentioned the existence of indecipherable signs that did not seem to correspond to any recognisable object: cup marks.

However, a few elements of this type were found in the fish shelter located in the Gorge d'Enfer valley, overlooking the right bank of the Vézère river (France).

In 1892, a ‘becquart’ salmon with an upturned jaw, characteristic of the male, was discovered carved into the ceiling of the vault. Dating back 25,000 years, it is believed to be one of the earliest known representations of fish in the world.

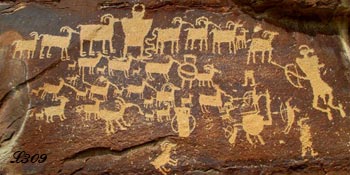

This type of notch is found on counting sticks, a mnemonic system used to record numbers by carving notches into a wooden or bone stick.

The origin of this technique dates back to the Upper Palaeolithic period, and several examples have survived :

- The Lebombo bone, a baboon fibula dating back more than 40,000 years BP, is the oldest evidence of human counting activity.

Lebombo bone.

- The Vestonice bone, dated to 30,000 years ago, was discovered in 1937 in the Czech Republic. It is a wolf bone with 57 notches.

Vestonice bone.

- Among the most famous counting sticks are the Ishango bones, discovered in the 1950s on the shores of Lake Edward in Congo. They feature a series of notches arranged in distinct groups, which have been the subject of numerous interpretations.

Ishango bone - Belgian Museum of Natural Sciences (-20,000 years).

Sticks of this type were used until the end of the 19th century to record various transactions.

e - Reality as depicted in cave paintings :

Lower Palaeolithic (approximately 800,000 to 300,000 BC)

Middle Palaeolithic (approximately 300,000 to 40,000 BC)

Upper Palaeolithic (approximately 40,000 to 9,500 BC), emergence of figurative art.

Mesolithic: 9,600 to 6,000 BC

Neolithic: 6,000 to 2,300 BC: Pottery

Bronze Age: 2,300 to 800 BC

Iron Age: 800 BC to 50 BC

Antiquity: 50 BC to 500 AD

Middle Ages: 500 to 1500

Modern era: 1500 to 1789

Contemporary era: 1789 to the present day

1 - The transition from Neanderthal to Sapiens :

The development of cave art marks a new stage in the development of means of expression.

Humans exploited the characteristics of their environment and used the dyes found there.

It was with Neandertals that this new artistic expression seems to have begun, which they may well have passed on to Homo Sapiens before disappearing around 30,000 years BP (before present).

Indeed, cave paintings dating back 65,000 years and recently discovered beads are believed to be the first works of art from the Neanderthal era. Today, although only Neanderthals occupied the region, a dozen murals created by them have been found in three caves in Spain.

Neanderthals have been identified in Spain (at Sima de los Huesos, Atapuerca) through fossils dating back 430,000 years, the oldest known to date.

Sapiens, on the other hand, did not arrive on the scene until around 45,000 years ago. Coming from the Near East, thanks to a relative improvement in the climate, they spread throughout Europe and coexisted for several thousand years with Neanderthals, until the latter became extinct.

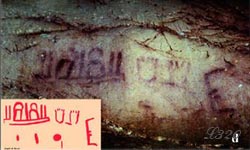

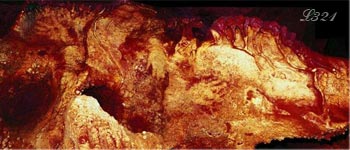

Red scalariform sign.

Thus, in the La Pasiega cave near Bilbao, around a ladder-shaped figure, there are dots, unidentified figures and representations of animals. A study using the uranium-thorium method has estimated the age of the paintings to be at least 64,800 years old.

Enlargement of the ladder-shaped representation

(current photo by Hoffmann on the left, survey carried out by Abbé Breuil in 1913 on the right).

(current photo by Hoffmann on the left, survey carried out by Abbé Breuil in 1913 on the right).

Key-shaped figure (La Pasiega cave).

Symbolic inscription and its survey on the left (La Pasiega).

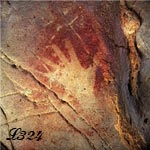

In the Maltravesio cave, the calcite deposited on negative handprints was dated using the uranium-thorium method. The minimum age of these handprints is estimated at 66,700 years.

If these results are confirmed, it could be suggested that Neanderthals were the inspiration behind cave art in Europe.

However, Christopher STRINGER (Natural History Museum) points out that the oldest traces of geometric figures (grids on ochre blocks) were made by Homo sapiens in South Africa 100,000 years ago.

Artistic expression therefore appears to have emerged simultaneously and in very distant places among different human species.

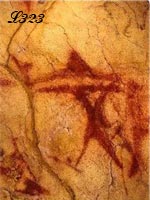

Therefore, if we consider that the Pasiega inscriptions are meaningful signs of a language, similar to representations of animals, we can see that Neanderthal symbolic development was very similar to that of Sapiens. Everything points to Neanderthals having the ability to communicate through language. All that remained was for them to develop their vocabulary, grammar and drawing skills, which their early disappearance prevented.

The gradual transition from Neanderthal to Homo sapiens art can be seen in other caves, also in Spain. At El Castillo, which was occupied between 120,000 years ago and the Bronze Age (1,000 years ago), a red stain has been dated to 40,800 years ago and a negative handprint to 37,300 years ago,

It is difficult to make sense of certain graphics, such as the claviform motifs in the Altamira cave. Described as symbolic for this reason, they can stimulate our imagination and allow us to see a bird or, by tilting the image, a hut built on a tree. Unless they are already the expression of a written language.

|

|

(Development of simple shapes: 3-4 years old)

Key-shaped figure dated to 35,600 years ago (Altamira Cave).

Key-shaped figure dated to 35,600 years ago (Altamira Cave).

Here, we could compare this image to the fortuitous realism evoked by G.H. Luquet (between random lines and the appearance of an object), around the age of 3.

While it is difficult to make sense of the diversity of images that follow one another over time, we can attempt to grasp the artist's psychological maturity through the expression of his drawing, when it becomes representative and accessible to us.

Expression of identity (14 to 18 months).

El Castillo Cave (-37,000 years).

El Castillo Cave (-37,000 years).

By placing his own hand on the wall, the artist momentarily abandons his view of the world to assert his own existence. The artist's representation of “his” hand could have the same meaning here as we give to a signature.

The emergence of representative drawing.

In the El Castillo cave, the panel of hands is accompanied by red stains from the Upper Paleolithic (-40,000) and a Magdalenian bison (-17,000). This panel shows the evolution of the peoples who succeeded one another over the millennia.

The artists who decorated this cave mark the transition from images with indeterminate meaning to representative drawings that establish a strong visual link with reality (4-5 years).

After what appears to represent the artistic transition from one human civilization to another, let's see how we might interpret the achievements of Homo sapiens.

2 - Individuality, community, and daily life in cave art :

The evolution of forms over time attests to the refinement of artists' ability to reproduce the surrounding world: the manual skills acquired in the field of toolmaking were directed toward drawing on a flat surface.

This skill is all the more evident as the use of color allows for representations that are increasingly close to reality. However, as the work depends on the artist, we will continue to adhere to a chronology based on the artistic maturity of the individual, regardless of the date of creation of these works.

We will nevertheless continue to mention the time and place of their creation in order to link the work to a moment in prehistory.

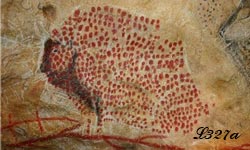

Alignment of dots at El Castillo.

- Gone is the hard work of digging cup marks; now colors take over, with a crucial advantage for future images and writing: speed of execution.

Representative drawing (4-5 years old).

Marsoulas Cave, Haute-Garonne, Pyrenees.

Marsoulas Cave, Haute-Garonne, Pyrenees.

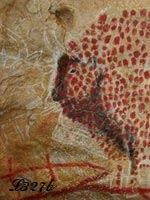

- Also forgotten are points such as undefined images or counting systems. Here, they are used to fill in and improve a drawing that has already been sketched out. In this image, three generations of artists seem to have succeeded one another. One sketches the outline of a bison with confident strokes (engraving by an experienced artist), the second completes the head and chest with shading and adds the eye and ear (painting by an experienced artist), and the last simply covers the whole thing with red spots (child aged 5 to 7).

At El Castillo, styles coexist on this panel, moving from symbolic images (on the left of the panel) to clumsy lines, then to a possible affirmation of identity.

Sketches of the paintings on the panel of hands.

These handprints indicate the use of tools, in this case a hollow object (bone or bamboo) to project the dye onto the wall after placing the hand or an ochre pencil between the two. Making these prints does not require fine control of hand movements, so artistic expression remains limited.

Furthermore, these prints could indicate the artists' lateralization, with the right hand being used most often.

(Affirmation of identity).

Hand in the Chauvet Cave - 36,000 years old.

The hand, isolated on the wall, may represent for the graffiti artist the affirmation of his identity and the occupation of a space dedicated to him that no one else can cover. The identity expressed here remains independent of the community.Hand in the Chauvet Cave - 36,000 years old.

Handprints at Cueva de las Manos in Argentina (between 13,000 and 7,000 years old).

Awareness of self and others (18 months).

On the contrary, a group of hands could indicate a strong sense of belonging to the community (14 to 18 months).Awareness of self and others (18 months).

Everyone shares a territory, and each person expresses their own personality within it.

The outline of the hands reflects this common identity, where each person leaves their own mark, with their own coloring and movement, while respecting the common direction. The guiding idea of one inspires all the others, and the pleasure is shared—the pleasure of living and creating together.

On this panel, a hierarchy seems to be established: in the lower part are the members of the tribe, and above them are the chiefs, who become fewer in number as their position rises.

We find in cave art the same stages of artistic development as those expressed in children's drawings and which we have been able to discover in the engravings.

|

|

Pedra Furada – Brazil (- 11,000 years BP).

Here we see the tadpole puppet (aged 4) again. The dotted filling is reminiscent of the hammering used in engravings.

Cueva de las Manos (Argentina). Negative hands and herd (-13,000 to -7,000).

At La Cueva de las Manos, childlike realism (ages 4-5) is enriched by the contributions of other artists, each expressing their own graphic mastery while sharing their discoveries in the world in which they live.

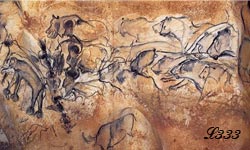

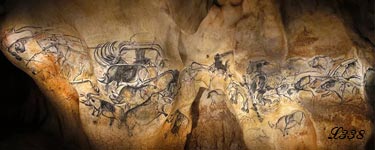

Panel of lionesses. Chauvet Caves (France) 37,000 to 28,000 years BP.

Multiplicity of detail and transparency, but perspective does not yet appear (ages 5 to 9).

The artist does not put himself in the picture. He narrates the life of the animal world, here it could be the hunt led by a family of lionesses.Multiplicity of detail and transparency, but perspective does not yet appear (ages 5 to 9).

It is worth noting that reality is respected: only lionesses participate in the hunt. However, the superimposition of drawings of varying quality suggests the involvement of several artists who drew inspiration from previous profiles. The artists find it more difficult to master entire animals.

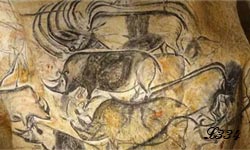

Rhinoceros in the Chauvet cave.

On this panel, as on the previous one, different works are superimposed, marking different stages of artistic maturity. Each artist imposes his own drawing, imitating or ignoring the successful or unsuccessful works of his predecessors. One of them imposes himself after erasing the underlying drawings, thus emphasizing the outline of his rhinoceros.

Altamira.

In the Altamira cave, dating back around 20,000 years, bison are depicted in bright colors, but they remain static. Each artist reveals their talent in a work that is intended to be collective, and each image fits into a space that respects the space of the others. However, these images do not form part of a collective movement: the drawing describes the animal in its attitudes, but ignores movement.

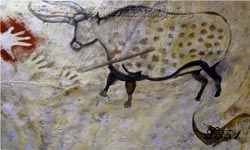

Lascaux Cave (between 21,000 and 21,500 years old). Descriptive drawing.

The drawing becomes more refined and several styles are expressed: transparency, filling with dots or color. The use of varied colors gives relief to the horse's body. The orientation is common: each artist takes his place among the previous works with his own style, bringing a herd to life.We discover the work of very different artists, some timid and occupying little space, partly covered by drawings that assert themselves through their strength and precision of line. Man observes an animal world that has not been domesticated.

Although apparently older, other paintings evoke a more organized collective life, where each character has their place in an earthly world, asserting their gender, function, and environment.

With domestication, the animal has lost its spontaneity.

This is a realistic drawing where humans and animals coexist.

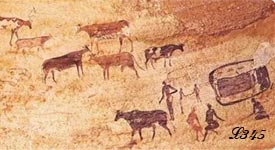

Bhimbetka-India.

Some of the prehistoric paintings found in the rock shelters of Bhimbetka, in the state of Madhya Pradesh, are around 30,000 years old. They are the oldest known rock art on the Indian subcontinent!Each character in the scene occupies a place that respects its environment. The description speaks of a peaceful community.

Elsewhere, the representation of reality appears abundant.

Group of rhinoceroses in the Chauvet Cave, (France), (30,000 to 32,000 years BP).

La précision des formes contraste avec l’aspect brouillon de l’ensemble des animaux représentés. Une rivalité transparaît entre chaque dessinateur, dans la copie et l’amélioration du tracé antérieur, l’effacement volontaire des images sous-jacentes ou les directions qui s’entrechoquent. This profusion can be compared to that of contemporary paintings on city walls.

Graffiti (present day) where creations overlap

and each artist attempts to showcase their style, or even impose it.

and each artist attempts to showcase their style, or even impose it.

3 - The expression of emotions in narrative drawing :

There are few complex images that can be attributed to Neanderthals. If we exclude the many symbols that remain incomprehensible and consider that each image corresponds to a word, this could indicate that their language was not very developed and their capacity for cooperation and communication limited, which could have been a weakness in a hostile environment and, perhaps, in the face of a dominant Homo sapiens.

We still see this today: in a conflict between peoples, the one who communicates best is most likely to win.

It is therefore the cave paintings of Homo sapiens that will now draw our attention. In addition to depicting scenes from everyday life, these paintings can express emotions. These appear in the context of narrative drawings, which reveal more than just a simple description of a character.

- Emotion and movement :

Serra da Capivara - Brazil (48,000 to 35,000 years ago).

Here, we see the emotion inspired by the mother protecting her young, that of the youngster frolicking joyfully, but also that of the shepherd seeing his flock grow.Happiness shines through in the naivety of the graphics.

The artist's inability to express movement restrains the emotion that could touch the observer.

- Attitudes towards hunting or warfare :

The variety of styles of images at Lascaux and other sites makes it difficult to attribute these works to a single culture. However, this variety allows us to experience a different feeling for each work, a feeling that is not that of an era, but that of the artist. In graphic expression, it is indeed the artist's life experience that we can find.

Lascaux (21,000 years old).

Thus, in this hunting scene, the artist has depicted, in the attitude of each character, his own life and his own experience of hunting within his tribe.

Altamira Cave - Spain (17,000 to 14,000 BC).

Here, the excitement is palpable in this unequal fight. The speed of the attack, the accuracy of the shot and the need to get away quickly are the conditions for survival.

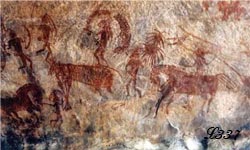

Tassili n'Ajjer - Algeria (10,000 to 9,000 years ago).

Another place, another scene : the solidarity of the tribe is expressed in the collective momentum and the will to win.- Serenity in everyday life :

Tassili n'Ajjer.

In contrast, serenity is expressed in this bucolic scene of everyday life.- Family portraits :

Elsewhere, a less skilled artist depicts the richness of life in the varied attitudes of the characters represented.

Magura Cave - Bulgaria (-9600 to -4000).

With the poses, the details (male sex) are not forgotten in this image: each character, clearly differentiated, seems alive. Although the artist did not depict a story, he was able to express his feelings for each member of his community, whether human or animal.

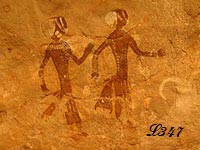

Tassili N'Ajjer - Algeria.

Elsewhere, certain characters stand out from the community. Are they a royal couple, or the artist's parents?We can see that the representation of the characters, seen in profile, is similar to the style developed in Egypt, without the richness of colour.

4 – The development of counting :

In the cave paintings, we find the symbolic marks that we discovered in the rock art in the form of holes (cupules) or vertical lines. The engraved dots are now replaced by a series of coloured spots or lines

Aurochs.

Salmon.

What do these symbols represent ? Are they numbers : for example, four dots for four aurochs or seven vertical lines for seven salmon ?

Furthermore, lines and dots have the advantage of being able to be added to as needed.

Their meaning seems to become clear when they accompany representations, but this is not always the case.

Swimming deer.

We know, for example, that the seven red dots above the ‘Swimming Deer’ frieze in Lascaux predate the deer. They cannot therefore be associated with them, and each graphic retains its own meaning.Let us continue our investigation.

Altamira Cave – Spain (14,000 years old).

Is this about livestock farming : would a herd then be indicated, with the dots representing the number of animals ? Or is it, on the contrary, a decorative ‘embellishment’ highlighting the animal ?There are many possible interpretations.

We can assume that the dots inspired a later artist, who inserted the tip of a spear thrown by the lower hand into one of them. The animal would no longer belong to a herd, but would be a wild animal.

As for the hands facing the animal, they could suggest the idea of protecting oneself from danger.

Whether the notches or dots constitute a counting system as we find today, or a decoration as we sometimes see, the answer still eludes us.

Nevertheless, we can be certain that the scenes depicted reveal that their creators possessed an intelligence as developed as our own. This intelligence enabled them to observe and discover, then describe through drawing, the world in which they lived.

While it is therefore possible to represent numbers, it is necessary to accurately date each painting in order to establish the correspondence between the possible number and the object or animal nearby.

If this is a counting system in the process of being developed, it would vary (dots or lines) according to the period and its creators and, for this reason, would be difficult to understand today.

As with the notches found on counting sticks, analogies can be drawn with current symbols: notches are often used by hunters who carve marks on their knives, or prisoners who carve lines on the walls of their cells, and dots are still used as a means of counting, as evidenced by the victory marks on aeroplanes.

Retired Israeli Mirage IIIC bearing 13 victory marks.

C – How can we interpret these early images :

How, then, can we understand this description of the world through images, before the emergence of our own description through the symbols of writing ?To achieve this, we must have a single goal in mind: to restore to the peoples who came before us their rightful place in the evolution of language. As we have already mentioned, these people were neither primitive nor magical beings from another world. They were simply people adapted to a time different from our own.

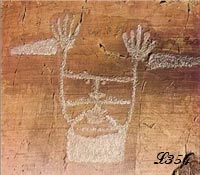

The image of the ‘sorcerer’ in the Valley of Marvels (but is he really a sorcerer?) could simply indicate the place where he was present.

The sorcerer - Petroglyph in the Valley of Marvels (-3000 to -1500 years ago).

But perhaps he was the shepherd from whom the tribe came to obtain milk or food: his raised arms could then be a signal to stop at this place.If we reflect on the lives of these men and their era, could their thoughts, expressed through drawing, prove to be communicable ? Furthermore, were these thoughts symbolic or simply concrete, adapted to everyday reality ?

Let us return to our sorcerer.

If we were to compare his image to children's drawings, we would think of the graphic maturity of a 3- to 4-year-old child.

However, we know that children, before being influenced by their social environment, are connected to reality. Evolution has not provided anything better to preserve life.

However, how can we understand that this « little tadpole man » has a head with arms but no legs ?

The people of the Vallée des Merveilles did not have mirrors, but they did have water sources for drinking and... seeing themselves. What do you see when you lean over a calm body of water ? You see your face and your arms moving around your head.

This petroglyph reminds us of the painting of Narcissus admiring his image in the water : it could therefore be the self-portrait of an unknown prehistoric man.

Do these drawings made by Homo sapiens deserve the label of artistic explosion that has been attributed to them, or should they simply be considered a step forward in the evolution of their manual skills ?

There is no shortage of hypotheses to explain the works of our ancestors. But it is essential to consider that, just as children refer to reality, early humans were content to represent the world around them as best they could.

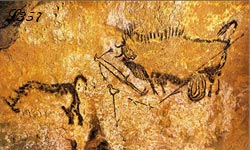

Let us now imagine another story told by a much-discussed scene in the Lascaux cave: that of a man lying on the ground, perhaps killed by an aurochs whose horns remain pointed at his body.

This image could be a warning of danger. The man lying down could be seen as a shaman defeated by a power greater than his own. He could also be sleeping and dreaming, as suggested by his erect penis.

All we can say for certain is that this is a man. Furthermore, depicted as a thérianthrope with his mouth open like his totem animal, he can be considered a ‘man of power’ within his tribe.

Let us try to reconstruct the scene with the help of these new elements.

(Retouched image)

Can a man alone, even a shaman, confront forces greater than those of his totem animal ?

(Original image)

Accompanied by his protective spirit, this man had come into contact with the animal world. Was it a friendly encounter or preparation for a hunt ?However, his totem, the bird, was not powerful enough to protect him from the charge of the aurochs.

He lost his life, and this event deserves to be drawn to warn and protect others, because certain forces of nature cannot be confronted by a man alone.

This representation marks the desire to remember and the human ability to anticipate future events.

Thus, all these drawings constitute an intermediate stage in communication. Beginning with sounds denoting danger, as we saw with Campbell's Mone, words appeared with the improvement of the articulation of these sounds. Later, images were able to represent words before writing made it possible to translate thought.

From sound to writing : the evolution of communication and representation of the world.

However, although images appear to be the first transposition of spoken language into graphic form, they can be difficult to understand for those who did not live in the era depicted by the scene.

Did we not struggle for centuries to understand the meaning of hieroglyphics before the Rosetta Stone taught us the equivalence between spoken language, images and written words ?

Before that, hypotheses prevailed.

What we can take away from this is that all these images, by illustrating real events, describe them in the same way that writing would later do.

Each image contains a set of information that can be understood by the person who created it, as well as those who experienced the event or live in the same context. If outsiders do not understand, the artist can explain it to them in words.

Toutefois, pour l’homme des temps modernes qui demande à comprendre, chaque élément de l’image demeure une énigme (pourquoi l’auroch ? pourquoi l’homme couché ?...).

The same is true today for adults who do not understand children's drawings, but he may then request an explanation.

« The image is a graphic representation that primarily concerns the person who created it.

It also concerns those who witnessed the same scene and can remember it.

Its meaning may be incomprehensible to outsiders who did not experience the event. »

It also concerns those who witnessed the same scene and can remember it.

Its meaning may be incomprehensible to outsiders who did not experience the event. »

We can see that all these images, so different from one another, tell us a story: the story of human evolution.

What would we discover if we could date each image in a cave ? Wouldn't that be a way of learning about the evolution of the groups that lived in this place over thousands of years ?

Each cave would then reveal to us those who passed through, inhabited and conquered it, and by comparing the images, we might learn which region of the world the group now inhabiting this place came from.

« L’image résiste au temps,

mais sa compréhension demeure limitée au vécu de l’artiste et de sa tribu. »

mais sa compréhension demeure limitée au vécu de l’artiste et de sa tribu. »

« Like spoken language, writing allows us to share a situation with as many people as possible.

Like images, it stands the test of time,

and what it expresses must also be translated in order to be understood by an even wider audience. »

Like images, it stands the test of time,

and what it expresses must also be translated in order to be understood by an even wider audience. »

From rock art to writing, the evolution of graphic design : (in french)

Bibliography :